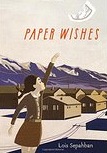

Paper Wishes follows a young Japanese-American girl, Manami, as she is uprooted from her life on Bainbridge Island to be interned with her family in Manzanar during World War II.

While the facts are historically accurate, Paper Wishes isn’t concerned with the larger context of xenophobia and the erosion of civil liberties. Instead, it is an intimate portrait of a girl who struggles with a profound sense of loss. When entering the camp, Manami had been forced to abandon the puppy that her grandfather had adopted, and the ensuing guilt plagues her. The misplaced guilt for something she isn’t responsible for is clearly meant to mirror the predicament of the interned Japanese Americans. Their loss of voice is symbolized in Manami’s literally being unable to speak in the camp. Her mode of communication is through drawings.

Manami narrates the book in short sentences, making the reading level suitable for a third grader. But for a child who feels a great deal of compassion for the protagonist, the events are likely to feel too sad. Manami’s mother loses her garden, her grandfather is struck listless and won’t go to the mess hall for meals, her brother Ron is jailed for what is deemed to be complicity in a riot, and her beloved dog doesn’t reappear even after all her paper wishes are sent off to him through the air. One positive note could be Manami’s discovery of a secret relationship between her teacher and her brother. But seen through Manami’s eyes, where it diminishes the special kinship she had felt with her teacher, it’s one more opportunity to feel bereft.

I haven’t yet tried this book out on a youngster. But my take on it as an adult is that Manami’s extreme sensitivity feels more like the writer’s projection of dismay about the injustices of Executive Order 9066 and less like the feelings that would naturally arise in a nine year old girl from the situation. Part of the mismatch for me stems from my father-in-law’s stories about Topaz from a 16 year old’s point of view. His memories about his time in internment camp were about his friends and activities there. He didn’t recall much sadness (but then he was an expert coper who leaned heavily toward denial.) Sadness at the time? No. Outrage at the situation later? Absolutely.